A trench coat-wearing maniac

stalks the Soho area of London, stabbing women with a switchblade. Inspector Rowan (Gilbert Wynne) can’t catch a break in the case, though he’s keen to

pin the murders on scuzzy lothario Pete (Donald

Sumpter). Meanwhile, Judge Lomax (Jack May) is having marital troubles,

and his job may be getting to him (these may not be mutually exclusive).

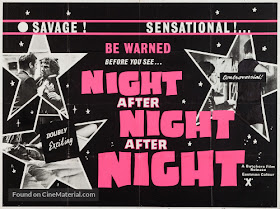

Lindsay Shonteff’s (under the Lewis

J. Force nom de guerre) Night After

Night After Night (aka He Kills Night

After Night After Night aka Night

Slasher) is an intriguing, if slightly confused film. It’s a sleazy sexploitation movie that

indulges in the most prurient imagery (there’s a rather blatant shot of a

stripper literally shaking her jugs at the camera) while stating that smut makes

“perverts” into killers. Simultaneously,

it’s about how the system (and by extension, the murderer) condemns and

punishes people for their sexuality while hypocritically desiring to satiate

its own erotic passions. Rowan and his

wife Jenny (Linda Marlowe) are the

most normal couple in the film. They

genuinely care about each other, and their relationship is fairly healthy. Jenny is the only major character in the film

who gets naked, and her sex scene with Rowan is loving, as are all of their

interactions. By contrast, Lomax and his

wife Helena’s (Justine Lord)

relationship is on the rocks. They now

sleep in separate bedrooms, and Helena even tries to reignite the old flame by

“behav[ing] like a whore” (this consists of donning some black lingerie). Lomax is completely disinterested, the daily

grind of “remov[ing] cancer from society” having eroded his emotions down to

stumps. Pete states that he practically

makes a career of “making birds.” He

flaunts his sexual exploits in Rowan’s face, telling him that he “banged” some

woman in the park “and she liked it.” He

taunts Rowan about Jenny, teasing that he’ll visit her and give her what she

needs (and what Rowan isn’t giving her [this is, of course, untrue; Pete’s just

trying to, and succeeding in, getting a rise out of Rowan]). Reducing Jenny to a receptacle for sex is

tantamount to a criminal act in Rowan’s eyes (most especially since it’s also

personal).

Pete is odious in his lascivious,

callous indifference towards his sexual partners and women in general, and it

is this, above all else, that makes Rowan (and the audience) hate him to the

point that he’s just dying to railroad Pete for the murders, guilty or

not. Rowan’s personal moral compass

overrides his duty to uphold the law and follow procedures. Likewise, Lomax despises the people who come

before him in court, handing out the harshest sentences possible like a

vengeful god, dispassionate toward extenuating circumstances. He would rather send someone to jail for the

maximum than get them hospitalized for mental issues or attempt to empathize in

any way with them. Lomax’s clerk Carter

(Terry Scully) surreptitiously reads

porn at work and frequents strip clubs.

Lomax admonishes him, “Overcome it, Carter, or it will destroy

you.” In Lomax’s mind, porn and rampant

sexuality are a scourge, and it must be dealt with in the most severe way

possible, but he stares at Jenny while dining at a restaurant, so we know that

he still has sexual urges hidden somewhere.

He’s just tamping them down, because to consciously acknowledge them

would be immoral. The extremes of

sexuality in the film (from unfettered to strangulated) are bad, morally and

criminally, and the line between the two is portrayed as pretty slim.

And yet, the film does not

hesitate to give the audience pulchritudinous female flesh at any given

turn. Aside from the aforementioned

stripper and the sex scene between Jenny and Rowan, we get things like a

gratuitous shot of the new undercover policewoman’s (Jacqueline Clarke) undies (go ahead and guess what she’s going

undercover as). We get an extended scene

of Pete getting laid out in a field while some repressed girl (maybe just shy;

Who the hell knows? She’s creepy,

regardless) watches. She then offers

herself to Pete, and he takes her up on it (talk about stamina). We get extended closeups of breasts being

groped and the like. There’s a queasy

complicity going on between the film and its target audience. We want to watch the sex and nudity; we’re no

different than the other men in the film.

Seeing these women killed because of the sexuality we desired to watch makes

us participants in their deaths in a way that doesn’t happen as much in later

slashers like the Friday the 13th

films and so forth. The difference, I

believe, is in the heavy moralizing the two main male characters engage in so

vociferously. This places a sobriety and

a sense of audience admonishment on the film, deserved or not. The constant sex thrown at us is the same

thing that created creatures like Pete and Lomax and instigated Rowan to go on

the rampage. So, while we’re being fed

it, we’re also being told that it’s bad for us, but it really isn’t, but it is.

Night After Night After Night is competently made, though its

pacing is a bit odd. Oftentimes,

adjacent scenes simply butt up against one another with no connective tissue

between them. It can be a little

jarring, but if anything, it actually adds to the film’s schizophrenic

ambience, continuing, in a way, to describe its juxtaposition of prurience and

prudishness. Even while being distinctly

British, there are Giallo elements at play, as well, making for something of

interest to devotees of that genre. The

killer wears a black leather trench coat.

There are POV shots of him stalking and stabbing his victims. There is the plain lurid quality so prevalent

in Gialli, including the close tying of violence with sex and how this affects

people mentally. However, the film is

simplistic to the point of being somewhat plain, and the finale meanders a bit

more than it excites. Nevertheless, it

kept my ass in my seat, and I never truly felt bored by it. Maybe I’m just another sex maniac.

MVT: The grittiness of the

film, augmented by its low budget aesthetics, is appealing, especially for

those of us for whom this is a big part of the attraction to films like this.

Make or Break: There’s a

character’s death rather early on that is not only surprising, but it’s also

surprisingly well-staged, and it sends the story in a different direction than

you might have initially expected.

Score: 6.75/10