In my personal opinion, mummies

have not been well used in cinema, generally speaking. I’m talking about the shambling, bandaged

(like a masking-tape-and-shoe-polish-decorated bottle a kid made for a grade

school art project) monstrosities here.

When it comes to these creatures, I prefer the kind that stalk over the

kind who scheme. Make no mistake, I

adore the hell out of Karloff’s turn

as Imhotep in 1932’s The Mummy, but

let’s face facts, all of us would have liked to have seen much more of Jack Pierce’s withered and enwrapped

makeup in action. Yet, mummies always

seem to get short shrift in the movies.

Rarely are they much more than unstoppable hulks (hypocritical as that

may sound based on what I just said), pawns of a more malevolent human with no

distinct personalities of their own (part of my problem with some of Universal’s

sequels to the Karl Freund film). Christopher

Lee managed to imbue loads of character to his turn as Kharis in Terence Fisher’s 1959 The Mummy, and even here, using only his

eyes and body movements, his onscreen rapport with Peter Cushing is evident. I’m

also a sucker for Paul Naschy’s gory

portrayal of Amenhotep in 1973’s The

Mummy’s Revenge (aka La Venganza de

la Momia), though if I really think about it, a lot of that film’s charm on

me comes from the divine Helga Line. But in Fred

Dekker’s otherwise fantastic The

Monster Squad (a movie I’m always surprised never elicits conversations

about the 1976 television series from which it takes its name), the mummy gets

a great character makeup which is barely seen at all and then is dispatched

almost offhandedly (this pisses me off to this day). Stephen

Sommers’ 1999 The Mummy did try to

develop their Imhotep into a more well-rounded character, but the film also

undercuts any of the menace of the monster by focusing more on action and

spectacle and cramming two pounds of horrid, computer-generated effects into

the proverbial one-pound bag (I’m not a fan of these films in the slightest,

and don’t even get me started on the same director’s Van Helsing). Thankfully, the

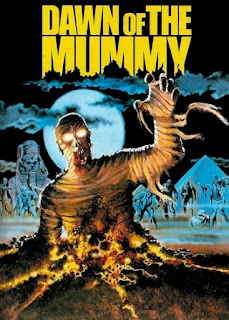

mummy Safiraman in Frank Agrama’s Dawn of the Mummy stays wrapped up and

desiccated for the film’s entirety, and he even gives off a fairly creepy, evil

vibe. Unfortunately, the vast majority

of the film and its participants are so godawful, it detracts massively from

the few (very few) good points it possesses.

In 3000 BC Egypt, the sadistic

Pharaoh Safiraman is entombed with the curse that if his resting place is

disturbed, both he and his army of slaves will rise up and kill. Cut to the present where jerk/tomb raider

Rick (George Peck) busts into said

tomb, preparing to rob it of its riches.

What better time than now for a wandering band of fashion models and their

photographer to show up and decide to use said tomb for a shooting

location? Needless to say, corpses are

disturbed, and murder ensues.

This is one of those films (much

like the previously-reviewed Maya)

where the Ugly American characters are so insanely overblown, you can’t wait

for them to die. Gary (John Salvo) is a narcissistic

pothead. Bill (Barry Sattels) is a narcissistic slave driver/boss. Melinda (Ellen

Faison) is a narcissistic horndog.

June (Diane Beatty) is just a

plain, old narcissist. They push their

way into the tomb and immediately set about desecrating every inch of the place

in pursuit of their commercial interests.

Watching the photo shoots set against the musty crypt nails home the

feeling of crassness these characters depict.

Their prioritizing of glamour and surface beauty only highlights their

shallowness (especially considering how one-dimensional they all are), and this

(more than Rick and his thieving cohorts) is what sets Safiraman off on his

rampage, in my opinion. The Americans

bring with them nothing but abrasive self-involvement, and this deserves death

in the film. Worse, the Americans’

effect on the local community marks those innocents for death as well in a

“guilt by association” way.

There are a couple of interesting

things going on in the film aside from this aforementioned theme, but they are

predominantly from a technical standpoint.

The shot where Safiraman rises is extremely effective, and, as stated,

the makeup and performance for the monster create a mildly intimidating aura

whenever he’s around. Additionally, it’s

somewhat refreshing to see a mummy film where the villain isn’t pining for some

long lost love who just so happens to bear a striking resemblance to the female

lead (yeah, it’s meant to give some depth to the character, but some on, the

trope is way overused). The scene of the

undead army (let’s just call them zombies, since they behave like zombies of

the Italian variety in every conceivable way, shape, and form) rising up is

loaded with atmosphere. There is a

nicely edited sequence which intercuts zombies attacking and eating people and revelers

dancing and partying at a wedding (the inconsequential character whose nuptials

these are is given an inordinate amount of time in the story). The gore is disgusting in the best possible

way, and the score by Shuki Levy

strikes a nice balance between traditional orchestration and funky pop.

Nonetheless, there’s far, far

more in the film to warrant passing on it (unless you truly savor garbage and

can stay awake for the duration). A lot

of this comes from the thespian skills of the cast which vary from moribund

(funny enough, this criticism doesn’t include the mummy and his army) to

Renfield-ian (in purest Arte Johnson

mode). In fact, I would be hard-pressed

to choose only one winner for the Robert

Marius Award in this movie, because the entire cast is truly worthy. Everyone seems to be mugging like Harpo Marx at almost every instant, and

when they’re not doing that, they’re grinning inappropriately at each other

like they’re wasted out of their minds (and hey, maybe they were). It gives the film an unhinged quality, but it

stinks more of incompetence rather than planned cinematic texturing.

And then there are the things

which simply boggled my mind. For

instance, how do set lights make a mummy’s body melt and wake him from his

eternal rest? How did the models pack

all of the shit they have with them on two horses and a jeep? If Safiraman’s slaves were originally killed

in his burial chamber, why are there no remains when the tomb is opened, and

why are the zombies rising up out of the desert rather than from the

sepulcher? Why does some random Egyptian

guy take to Gary and invite him to his wedding just because Gary shows up to

smoke some weed at this guy’s café? Why

does Rick wake Melinda up in the middle of the night to get some after she’s

fainted from stress a very short while ago (okay, this one I could kind of understand,

but it’s placement in the film is just odd)?

Why does Rick allow Bill and the models to boss him around when he could

merely kill them all and bury them in the desert (or let the scavengers pick

them apart, which also brings up the question of how a Bedouin’s decapitated head

managed to last as long as it did without being gnawed at or buried in the

shifting sands)? It’s not so much that

the film raises questions like this in a viewer’s mind; it’s that these

questions become more intriguing (and distracting) than the film itself. If you can answer any of these questions, or

if you’re okay with what they conjure in your mind, this might be the movie for

you. Everyone else can leave this one

buried.

MVT: The untethered property

of the film certainly makes it stand out as an oddity, for sure.

Make or Break: By about the

second or third scene involving Rick and his gang, I realized that the way

these people were acting was intentional.

Score: 3/10

No comments:

Post a Comment