Hondo (Akira Kobayashi), a battlefield photographer, meets cute with

Yoriko (Chieko Matsubara), a

stewardess, and the two decide to spend some time together. Little does Hondo know that Yoriko is wanted

by no less than four nefarious groups (three of them straight up gangsters plus

the titular ninja team) for information she may have in regards to her father

and his legacy.

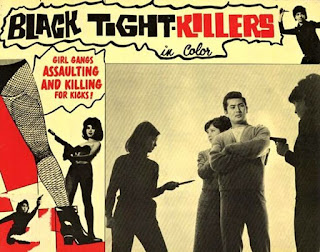

Yasuharu Hasebe’s Black Tight

Killers (aka Ore Ni Sawaru To

Abunaize aka Don’t Touch Me I’m

Dangerous aka If You Touch Me Danger)

is a film that I’m sure people would claim owes a ton to the work of Seijun Suzuki, especially Branded to Kill and Tokyo Drifter, if they didn’t know any better. Thing is, Drifter

was released the same year as this one, and Branded was released the following year. But the films do bear a striking resemblance

in terms of style, if not necessarily in their approach to narrative. Black

Tight Killers is much more traditional in story structure like the more

nailed down rock ‘n roll used in the film while its aesthetic is pure artsy

freestyle jazz (also used in the film).

This combination makes the film a little more approachable than some of Suzuki’s more outré work. Black

Tight Killers is a hepcat’s action fantasy with Kobayashi (one of Nikkatsu Studios’ “Diamond Guys”) as its ginchy ring

leader. The film is full-on garish

excess most of the time, experimenting with form and directly applying art to

create a unique cinematic world (something which was very much on the rise in

Japan at the time, I believe). For

example, the rear-projected background in a night driving scene is tinted dark

blue, but when the car enters a tunnel, it changes to orange-yellow. A street at night (filmed on a set) is

nothing but black silhouettes of buildings, the only details the bright neon

signage of the clubs that litter the city.

A dream sequence becomes an extended fantasy sequence, as Yoriko is

chased across sets decorated with nothing other than the saturated colors of

their boundaries.

This unorthodox approach gives

way to a more exploitative fashion in the actual narrative. The gangsters are the kind that George Reeves’ Superman would have

burst through a wall to thwart. They’re

all ugly as sin and mean as wolverines.

They tie up, strip, and torture the women in the film at several

points. One female is chained up and

painted silver (the paint will suffocate her, of course). One female is chained up over a pool of water

and wired with electrodes. You get the

picture. More than these, however, it’s the

Black Tights who have the wildest moments imaginable. Their form of Ninjitsu is idiosyncratic, to

say the least. They employ weapons such

as razor sharp tape measures (yes, really), ninja chewing gum bullets (yes,

really), and 45 RPM records that they hurl like shuriken (yes, really). Their actual physical techniques extend to

voice impressions, the requisite kicking, punching, and thigh chokeholds, as

well as something called the Octopus Pot technique, about which I will say no

more so you can discover its glories for yourself. Hasebe

combines forthright action tropes with the more abstracted artistry of this

universe, and the two produce a quasi-freeform union that carries the film

along nicely. This marriage is, very

arguably, no better displayed than in the death scene of a character towards

the film’s end. As the character dies, a

pool of brilliant blue paint pours into frame on the ground below, not only an

artificial representation of said character’s blood, but also a statement that

this character is as much a work of art as any of the ultra-stylized settings

we’ve seen.

So let’s discuss some of these

characters. Our male lead, Hondo, is

part womanizer, part man of action, all casual attitude. He’s intended to be a groovy daredevil, but

his charms are so slight, he’s practically a non-entity. Even more of a cipher is Yoriko, a

quintessential damsel in distress. She

has no personality to speak of except that she loves Hondo for some

inexplicable reason (this does have a nice payoff at the end, but it’s a bright

spot on a dull polish job), and her secret is what drives the plot. Fused together, the leads barely provide

enough interest to buoy the film above drowning level. The gangsters, as previously mentioned, are

the standard issue thugs we’ve come to know and loathe from movies of this time

and place. They are skanky, underhanded,

and visually striking. And that’s about

it. The real core of the film is the

Black Tights, yet even they are hardly distinguishable from one another except

in the looks department (my favorite is Natsuko [Kaoru Hama], but that’s neither here nor there), partially because

they dress the same (down to the Red Star Lilies they all wear on their leather

coats), partially because none of them really has a personality to differentiate

one from another (while they each get individual scenes to alternately

antagonize and fall in love with Hondo, the only one of these that stands out

for very specific reasons is the one with Akiko [Akemi Kita], but all of them are more situation-based than

character-based). They have a

purpose. This, to my mind, is the point. The Black Tights aren’t meant to be different

people but one (moreso than the indistinct villains), a sort of gestalt representing

where they came from, and that representation represents the demarcation between

noble and ignoble, in light of certain events.

In all honesty, Black Tight Killers is nothing to write

home about if taken strictly on the virtues of its story. It’s as by the numbers as these things get

(with the very slight exception of old coot Momochi’s [Bokuzen Hidari] underserved Ninja Research Society). The action is fairly well-handled, though

some of the hand-to-hand stuff involving the Black Tights looks like they’re

playing rather than fighting (come to think of it, that might not be such a bad

idea). Truly, the film lives or dies on

its style, and in that department, it excels.

Whether they’re dancing at one of the local go-go clubs or picking

fights with guys twice their size, the Black Tights exemplify the Swingin’

Sixties in Japan about as well as any other pop-art-influenced film does. The chances Hasebe takes as to how he tells his tale (actually, one based on a Michio Tsuzuki novel, but why quibble?)

are what sets the film apart marvelously, like the bright orange flowers of the

ninja femmes set off the basic black leather canvases of their apparel.

MVT: The eponymous ladies

are both the show and the showstopper.

Make or Break: If you can’t

make it through the dance sequence playing behind the opening credits, you

won’t like this movie. If you do like

it, you’ll know you’re right where you need to be.

Score: 7/10

No comments:

Post a Comment