Jasper Hawks (John Carradine) and

his feckless poltroon of a partner Elmer (John Mitchum, brother of Robert) tool

the backwoods area of (let’s assume) the Pacific Northwest with their carload

of tchotchkes and junk. Meanwhile, Joi

(Joi Lansing) is a pilot whose plane crashes in the same mountainous area where

she is summarily captured by a Bigfoot.

Also meanwhile, motorcycle enthusiast Rick’s (Chris Mitchum, son of

Robert) girlfriend Chris (the fulsomely bestowed, beauteous Judith Jordan) is likewise

kidnapped by a Bigfoot. Chris and Joi

are held captive while everyone else does a lot of talking and walking in their

search for them.

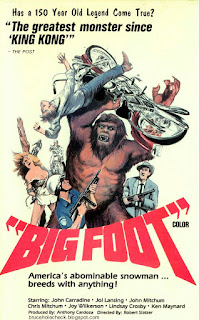

Robert F Slatzer’s Bigfoot does its damnedest to capitalize

on the then-recently released Patterson-Gimlin footage of a Bigfoot sloping

around Bluff Creek in Northern California.

Admittedly, the country had gone Bigfoot Crazy, and the beast (and

regional variations thereof) swiftly became as much a pop culture icon as it

was a figure of myth and speculation (this carries through to today, though in

far more cynical fashion). The first

thing that struck me while watching this film was how much it reminded me of

1972’s The Curse of Bigfoot. The resemblance is not so much in narrative content

aside from the subject matter. While I

haven’t seen Curse probably since I

was a kid, I clearly recall three things about it. One, its finale (monster movie endings back

then were straightforward). Two, the

monster was discovered wrapped like a mummy in a Native American burial

mound. Three, the monster makeup looked

like a giant meatball that someone had dropped into a pile of dog hair and

rolled around for a bit, then slapped eyes and fangs on it (and it had a habit

of walking directly at the camera as a sort of transitional device).

Bigfoot shares two of these traits, specifically. First, the monster makeup is horrible

(though, in fairness, better than that in Curse),

consisting of an immobile rubber mask and an ill-fitting fur suit. The kid Bigfoot simply has some black stage

makeup around his eyes and nose. It’s

almost sad, really, these yearnings for more Pakuni-esque makeup effects that

this thing evokes. Second, is the

creature’s ties to Native American culture and its own tribal structure. The characters come upon what they take to be

an Indian burial ground, but they find a dead Bigfoot in a shallow grave. Later, a Native American woman, upon hearing

of the monster, utters the word “Sasquatch,” thus giving the film a bit of

cultural diversity (no, not really). The

Bigfeet are dying off, the same as the Native American tribes had been for a

long, long time but had somehow only around this era really become a topic of

discussion in pop culture and media in general.

Like the Stick Indians (the more maladjusted version of the Bigfoot

legend in Native American mythology), these Bigfeet steal women in order to

breed with them. In essence, they play

the role of savages that Native Americans occupied in many a Western. Of course, all of this takes a back seat to

the rip-roaring excitement of walking and talking or getting the latest on

Sheriff Cyrus’ (James Craig) love life with Nellie (Dorothy Keller) down at the

local store.

Likewise, the film calls back

hard to 1933’s seminal King Kong as

well as 1740’s Beauty and the Beast (to

which Kong also calls back). In the opening credits, the creature is

billed as “The Eighth Wonder of the World,” just like Kong. After the film’s climax, Jasper laments that

“It was Beauty killed the Beast.” This

wouldn’t be so egregious if it weren’t so wrongheaded. Certainly, comparisons can be made between

Jasper and Carl Denham, but the Carradine character is portrayed as avaricious

and opportunistic to an almost villainous degree (plus, he’s really mean to

Elmer). Denham, at least as played by

Robert Armstrong, had a fatherly, caretaking connection to Ann Darrow,

motivating his sometimes-selfless acts in the efforts to rescue her. Yes, he could be myopic in his lust for fame

and fortune, but he wasn’t a total jerk.

What’s intriguing in this movie

is the idea of bestiality and sex in general which it puts at the

forefront. Joi and Chris are being held

specifically to have sex with the male Bigfoot and carry on its bloodline (Joi

somehow intuits this as if she were Jane Goodall). Further than this, the two actresses’

pulchritude is prominently on display throughout. By 1969, depictions of sex on screen had

become much more graphic, yet Slatzer and company never go the extra mile into

pure exploitation. It feels as though

they wanted to have just enough salacious teasing for the teenagers in the

audience (which also explains the “biker” angle, and yes, that word should be

in quotes with regard to this film) while also being chaste enough that parents

could take their families to see it.

Like the beasts in the movie, the audience is allowed to get fired up

about the possibilities available for sex in the film but will ultimately be

denied the experience, even vicariously.

Add to this the fact that the Bigfeet have no discernible

personalities. They are pure animals,

acting on vicious instinct, and this robs the film of any empathy we may have

about their plight. Unlike Kong or the

Beast, who formed connections with their captives and made us care about the

deep emotions that undo them, the Bigfeet are the proverbial pack of rabid dogs

in need of putting down. But, then, to

expect more from this movie is to not understand it.

Slatzer varies scenes shot on

location with scenes shot on stage sets.

The country store is perhaps the best lit (in a fake sense) one of its

kind ever put on screen. These staged

scenes serve to give the movie the feeling of something made for

television. One can understand this, as

indoor sets are far easier to control from a technical perspective, but their

insertion here undermines (or augments, depending on your point of view) any of

the low budget charm this film could have had.

It’s too sterile, too unnatural.

I can guess why the filmmakers chose to shoot so much filler of people ambling

through forests or motorcycling through forests or chatting in forests. It’s cheap and easy. But I would surmise that most people would

want to see this thing for a little bit of skin (a very little bit) and some

Bigfoot action. Watching actors (even

the great Carradine) spout variations on the same theme over and over again

with the occasional glimpse of what you’re anticipating feels more like a carny

cheat (and maybe Slatzer worked in carnivals, I don’t know) than the buildup

and payoff that an audience would actually want. At least the Patterson-Gimlin footage got it

right. It’s roughly two minutes of what

people desire: to have their sense of awe and wonder stoked. Bigfoot

is the equivalent of roughly ninety minutes of moving furniture, and who

desires that?

MVT: The idea isn’t

bad. It just never lives up to the

come-on of its advertising.

Make or Break: The extended

scene of Cyrus and Nellie discussing the local goings-on in their neck of the

woods about which no viewer in their right mind would give even the slightest

shit.

Score: 3/10

No comments:

Post a Comment